Los físicos desentrañan el misterio de larga data de las ondas atrapadas

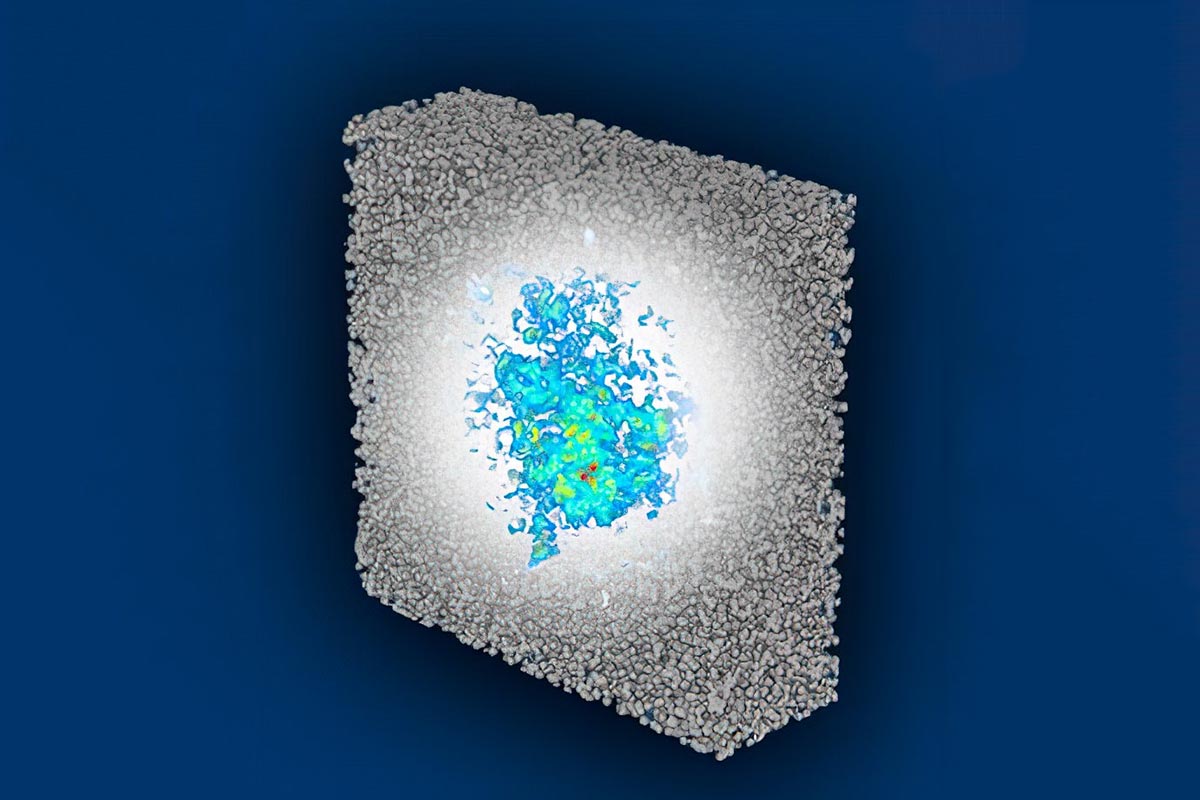

La computación avanzada ha ayudado a los investigadores a resolver un misterio de décadas sobre la ubicación de la luz en las estructuras 3D. El estudio encontró que la luz puede quedar atrapada o «localizada» en paquetes aleatorios de esferas metálicas, allanando el camino para posibles desarrollos en láseres y fotocatalizadores. Crédito: Universidad de Yale

Un equipo de investigadores ha aprovechado un aumento notable en el poder de cómputo para resolver un misterio de décadas sobre el potencial de las ondas ópticas para quedar atrapadas en estructuras tridimensionales de micro o nanopartículas empaquetadas al azar. Este descubrimiento innovador podría conducir a avances en láseres y fotocatalizadores, entre otras aplicaciones.

Los electrones dentro de un material pueden moverse libremente para conducir corriente o quedar atrapados y actuar como aislante. Esto depende de cuántos defectos distribuidos aleatoriamente tenga el material. Cuando este concepto, conocido como localización de Anderson, fue propuesto en 1958 por Philip W. Anderson, resultó ser un punto de inflexión en la física condensada contemporánea. La teoría se ha extendido a los reinos cuántico y clásico, incluidos los electrones, las ondas acústicas, el agua y la gravedad.

Sin embargo, no está claro exactamente cómo funciona este principio para capturar o localizar ondas electromagnéticas en tres dimensiones, a pesar de 40 años de extenso estudio. Dirigido por el prof. Hui Cao, los investigadores finalmente han proporcionado una respuesta definitiva sobre si la luz se puede localizar en tres dimensiones. Es un descubrimiento que podría abrir una amplia gama de vías tanto en la investigación fundamental como en aplicaciones prácticas utilizando luz localizada 3D. Los resultados se publicaron el 15 de junio en el The quest for 3D Anderson localization of the electromagnetic waves has spanned several decades with numerous attempts and failures. There were multiple experimental reports of 3D light localization, but they were all questioned due to experimental artifacts, or the observed phenomena were attributed to physical effects other than localization. These failures led to an intense debate on whether Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves even exists in 3D random systems. Since it is extremely difficult to eliminate all experimental artifacts to get conclusive results, Cao and her coworkers resorted to the “indignity of numerical simulation,” as Philip W. Anderson put it in his 1977 Nobel Prize lecture. However, running computer simulations of Anderson localization in three-dimensions has long proved challenging.

“We could not simulate large, three-dimensional systems because we don’t have enough computing power and memory,” said Cao, the John C. Malone Professor of Applied Physics and Professor of Electrical Engineering and of Physics. “And people have been trying various numerical methods. But it was not possible to simulate such a large system to really show whether there is localization or not.”

But then Cao’s team recently teamed up with Flexcompute, a company that had a recent breakthrough in accelerating numerical solutions by orders of magnitude with their FDTD Software Tidy3D.

“It’s amazing how fast the Flexcompute numerical solver runs,” she said. “Some simulations that we expect would take days to do, it can do in just 30 minutes. This allows us to simulate many different random configurations, different system sizes, and different structural parameters to see whether we can get three-dimensional localization of light.”

Cao assembled an international team that included her longtime collaborator Prof. Alexey Yamilov at Missouri University of Science and Technology and Dr. Sergey Skipetrov from University of Grenoble Alpes in France. They worked closely with Prof. Zongfu Yu at University of Wisconsin, Dr. Tyler Hughes, and Dr. Momchil Minkov at Flexcompute.

Free of all artifacts that have previously marred experimental data, their study closes the long debate about the possibility of light localization in three dimensions with accurate numerical results. First, they showed that it is impossible to localize light in three-dimensional random aggregates of particles made of dielectric materials such as glass or silicon, which explained the failures of the intense experimental efforts in the past several decades. Secondly, they presented the unambiguous evidence of Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves in random packings of metallic spheres.

“When we saw Anderson localization in the numerical simulation, we were thrilled,” Cao said. “It was incredible, considering that there has been such a long pursuit by the scientific community.”

Metallic systems have long been ignored due to their absorption of light. But even considering the loss of common metals such as aluminum, silver and copper, Anderson localization persists.

“Surprisingly, even though the loss was not small, we can still see the evidence of Anderson localization. That means this is a very robust and strong effect.”

Besides resolving some long-standing questions, the research opens new possibilities for lasers and photocatalysts.

“Three-dimensional confinement of light in porous metals can enhance optical nonlinearities, light-matter interactions, and control random lasing as well as targeted energy deposition.” Cao said. “So we expect there could be a lot of applications.”

Reference: “Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves in three dimensions” by Alexey Yamilov, Sergey E. Skipetrov, Tyler W. Hughes, Momchil Minkov, Zongfu Yu and Hui Cao, 15 June 2023, Nature Physics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41567-023-02091-7