Dos burbujas masivas en el manto de la Tierra desconciertan a los científicos con sus asombrosas propiedades

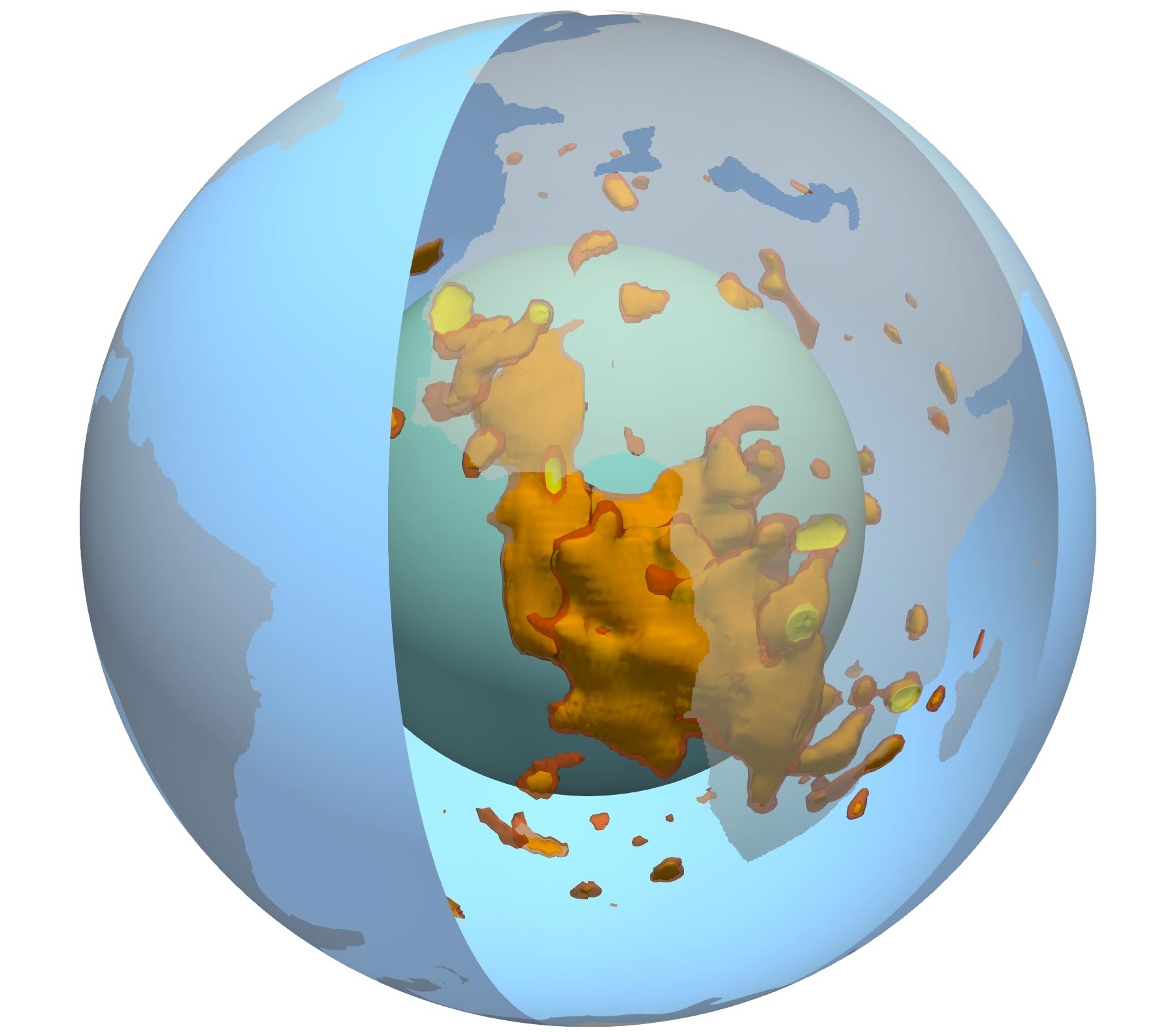

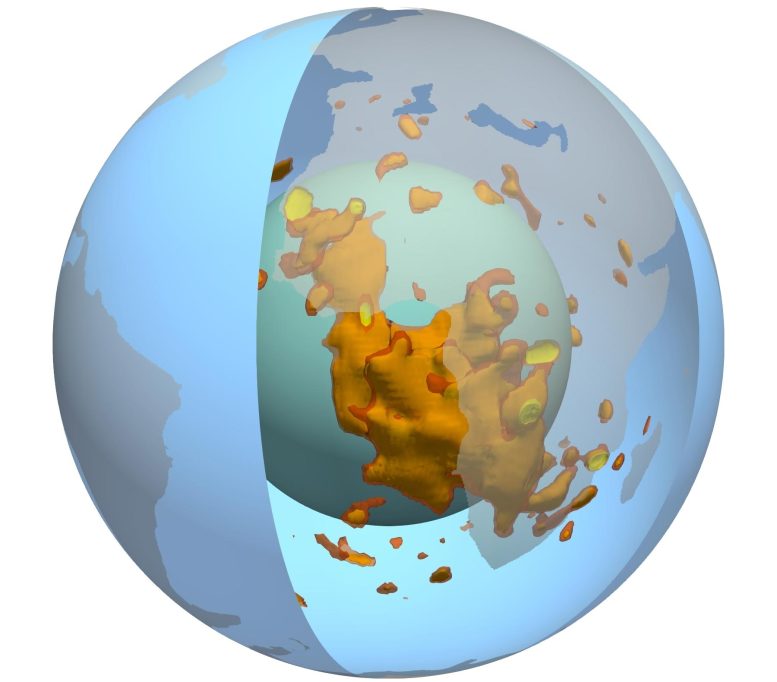

Una vista en 3D de la burbuja en el manto de la Tierra debajo de África, mostrada en colores rojo, amarillo y naranja. El cian representa el límite entre el núcleo y el manto, el azul significa la superficie y el gris transparente significa continentes. Crédito: Mingming Li/ASU

La Tierra tiene capas como una cebolla, con una corteza externa delgada, un manto grueso y viscoso, un núcleo externo fluido y un núcleo interno sólido. Dentro del manto, hay dos estructuras masivas similares a burbujas, aproximadamente en lados opuestos del planeta. Las burbujas, más formalmente llamadas Grandes Provincias de Baja Velocidad de Corte (LLSVP), son cada una del tamaño de un continente y 100 veces más altas que el Monte Everest. Uno está bajo el continente africano mientras que el otro está bajo el Océano Pacífico.

Usando instrumentos que miden las ondas sísmicas, los científicos saben que estas dos burbujas tienen formas y estructuras complicadas, pero a pesar de sus características prominentes, se sabe poco sobre por qué existen las burbujas o qué llevó a sus formas extrañas.

Los científicos de la Universidad Estatal de Arizona Qian Yuan y Mingming Li de la Escuela de Exploración de la Tierra y el Espacio decidieron aprender más sobre estas dos burbujas utilizando modelos geodinámicos y análisis de estudios sísmicos publicados. A través de su investigación, pudieron determinar las alturas máximas que alcanzan las burbujas y cómo el volumen y la densidad de las burbujas, así como la viscosidad circundante en el manto, pueden controlar su altura. Su investigación fue publicada recientemente en

The results of their seismic analysis led to a surprising discovery that the blob under the African continent is about 621 miles (1,000 km) higher than the blob under the Pacific Ocean. According to Yuan and Li, the best explanation for the vast height difference between the two is that the blob under the African continent is less dense (and therefore less stable) than the one under the Pacific Ocean.

To conduct their research, Yuan and Li designed and ran hundreds of mantle convection models simulations. They exhaustively tested the effects of key factors that may affect the height of the blobs, including the volume of the blobs and the contrasts of density and viscosity of the blobs compared with their surroundings. They found that to explain the large differences of height between the two blobs, the one under the African continent must be of a lower density than that of the blob under the Pacific Ocean, indicating that the two may have different composition and evolution.

“Our calculations found that the initial volume of the blobs does not affect their height,” lead author Yuan said. “The height of the blobs is mostly controlled by how dense they are and the viscosity of the surrounding mantle.”

“The Africa LLVP may have been rising in recent geological time,” co-author Li added. “This may explain the elevating surface topography and intense volcanism in eastern Africa.”

These findings may fundamentally change the way scientists think about the deep mantle processes and how they can affect the surface of the Earth. The unstable nature of the blob under the African continent, for example, may be related to continental changes in topography, gravity, surface volcanism and plate motion.

“Our combination of the analysis of seismic results and the geodynamic modeling provides new insights on the nature of the Earth’s largest structures in the deep interior and their interaction with the surrounding mantle,” Yuan said. “This work has far-reaching implications for scientists trying to understand the present-day status and the evolution of the deep mantle structure, and the nature of mantle convection.”

Reference: “Instability of the African large low-shear-wave-velocity province due to its low intrinsic density” by Qian Yuan and Mingming Li, 10 March 2022, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-022-00908-3